New York, Upper East Side: “Are you here to see the Rebbe?” someone asks, a guy I haven’t seen in maybe a decade, shouting over five or six heads in the two or three feet of space between us.

It’s a crowded, windowless basement, deep in a part of Manhattan I never expected to find myself in. I got off the subway near the 59th Street Bridge, which may have been where Simon & Garfunkel hung out 50 years ago but now is just a neat mess of shiny apartment buildings, most decked out with holly for the season with a few darkened windows where there’s probably Jews hiding.

My teacher from yeshiva, Leibish, who’s just taken over from the tzaddik Sholom Brodt, was speaking. A band I really like was arranged to play. I had a work event late; I’d be in the city anyway, and I’d been a little antisocial lately but my best friend in town was moving to Texas so I might as well force myself to stay out a bit, right?

The apartment on the invite was dead. The doorman looked at me askew, but I told him the number and he called up once — no answer — but he tried again and he said into the phone, “Niccolo, someone named Matthue to see you?”

Now, when you’re not just Jewish but Orthodox, and not just Orthodox but into weird hippie mystical occult stuff, there aren’t too many people with names like Niccolo. There aren’t many Matthues, either, and I recognized the name as one I’d heard in Crown Heights, one Purim several years back, when he asked what kind of Hasid I was and I said Biala Ostrova and he literally fell on the floor in surprise because he was, too, and there aren’t too many of us in the world. The joke is, most Hasidic rebbes show up with a carful of followers; in Biala, you get a follower and a car full of rebbes.

He tells the concierge, the class is somewhere else, and it’s a cold night so I don’t blame him for staying home but I say, “Could you tell him Matthue says hi?” and the guy looks at me like, what are you, in fifth grade, and asks if I just want to talk. I take the phone, hungering for that little bit of connection, and he says, “Good to hear you, brother, I’ll see you in a few minutes, right?” and I figure I’ve misread the situation and I figure I’d better take the address and start walking.

It’s 18 blocks and an avenue or two. I’ve been out of Manhattan nights so long the numbers don’t naked any sense to me and I don’t know whether the walk is normal or ridiculous, but it’s to see Leibish, which is worth a little sacrifice. Along the way I pass diners, old men in jeff caps walking tiny dogs, single people crying or laughing into phones, and it’s so cold you can’t tell which and maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe a hundred years ago I would’ve stopped to ask if they were okay, but tonight I’m already an hour late, I’m no longer good with people, I’m not looking for adventures, just a way to get home as early as possible — I have to be up for the kids — and I don’t know where I’m going, and it occurs to me that the new address has no apartment number, an impossibility in this neighborhood.

I walk there, and I walk past it, and there on the basement door is the number of the place. The plaque says BOMA and there’s no windows, but there is singing, and I go in.

The room is packed. A wall of tall potted plants separates men from women. There are guys with long beards and guys with no beards, guys in black and white and guys in crosshatched business shirts, guys with empty plates, guys still stuffing their faces. The smell of kugel hangs rich in the air, this bubbling hot pudding of pulverized potatoes and onions and oil, and it’s the most addictive thing in the world, like French fries mixed with cocaine, and a whole mosh pit separates me from the kitchen, but getting some is the furthest thing from my mind.

Leibish is talking.

He’s gray now. His beard is an upside-down Afro, his payos are frizzy antennae plugged into another world, and his voice has not aged a day, that half-singing, half-whispering voice like he’s always about to tell you a secret.

“The yud in G-d’s name, the י, is infinity. The black part of the letter is just a dot, it’s almost all white. The next letter hay, the ה, is the space we have to make for G-d in this world, not the world of infinity, but how we harness that infinity and constrict it and bring it into our lives. Like, this world is nothing! You can’t take it too seriously! Here, I’m going to tell you a joke. Let me think of a joke.”

This is what I crossed the city for. It’s already 9 p.m., I’m barely going to stay here an hour, but if all I get is this moment of Leibish and his Torah, that’s all I need, that’s what I was meant to be here for.

He speaks, and he speaks for a while, and then we move into the basement apartment next door, where the band is setting up. Someone hands Leibish his saxophone and it sort of swings around his body. He contorts into it, like Coltrane, like a baby spooning its mother. And maybe this is the time I get up and start thinking about the potato kugel upstairs? Except I’m probably volunteering to help move stuff. Carrying the microphone stands like harpoons, swinging two chairs on each hip almost like I know what I’m doing. Down the stairs, back up again.

“Are you here to see the Rebbe?”

I forget his name. Someone I haven’t seen in a decade. The place is even more packed, if that’s possible. The Rebbe? Which rebbe? I didn’t even have to ask. I knew which rebbe.

“Which rebbe?”

I asked anyway. These days, I think, I am too much hay with not enough yud, all contraction and no infinity. I get done what needs to get done. It’s getting late. Bedtime is calling.

“The holy Ostrova Biala Rebbe! You know him, don’t you?”

That’s one way to say it. When I was in Israel, pulled there by a new wife and father-in-law whose motives I had yet to completely grok, I resented Israel for not being San Francisco. Then I started in the yeshiva where Leibish taught, and at night one of my teachers would take me to the office of the Ostrova Biala Rebbe, where we waited for hours for him to repeat our names over and over again, give us advice for love and jobs and friends and art, pray with us, and pinch our cheeks with a grip that was alarmingly firm.

“He’s here? In New York?”

“In this apartment, in the back room.”

I ran to the back room. The door was shut, of course. In front of it was Niccolo, who had stood back up since the last time we met. “Is the Rebbe here?” I gasped out, breathless.

He told me he was. He told me I could see him. He told me there was just one person in line, just as a short Israeli woman left, together with her interpreter, and half a dozen people leaped from all corners of the apartment to bum rush the door.

Niccolo stepped in. He had all the decorum and reserve of a documentary moderator. “Now, who has an appointment,” he said, “and who just wants a blessing?”

A blessing seemed like the 10-items-or-less express lane. I would take a blessing. That’s all I really wanted, right? To be blessed.

We waited. The quickie blessings seemed not to be so quick. In the meantime, the as-yet-unblessed of us hung out outside, talking, trading stories, figuring out where we knew each other from. I freaked. My friend Hillel, who when we used to hang out were both Kafka nerds and now he’s in charge of a whole school, hundreds of kids’ minds being formed by him, talked me down. “Don’t prepare things to ask about or things you want to tell him,” he said. “Just let it happen.”

“Be the hay,” I agreed.

It was my time, and I went in. Niccolo, who I realized somewhere in the waiting was actually the conductor of this whole operation, the concert that was still going downstairs and the Rebbe and his stalkers, stayed inside. In part of my aforementioned freakout, I remembered in a rush that the Rebbe only spoke Hebrew, and then I remembered that I spoke no Hebrew.

And then we were face to face.

I’m not going to tell you what we talked about. I will tell you that he said shehechiyanu, the prayer that you say on special occasions, when he saw me. I’ll tell you that he made me say my family’s names, including all my kids’ ridiculously long full Hebrew names, and he said “is that it?” when I was finished. We talked for two minutes. We talked for an eternity. We laughed a lot, and I can’t remember at all why we were laughing.

He said something that made Niccolo and I both jump up and down. He didn’t pinch my face, but he slapped my cheek, several times, hard, and I literally lost my balance. (Full disclosure: I’d been up since 6, and blowing on me might have made me lose my balance at that point.) He said one thing that was totally unexpected, that I’d only been thinking about for a day or two, and when he said it he looked surprised and turned to Niccolo. Niccolo didn’t look surprised at all. “Rebbe, of course you knew,” he said.

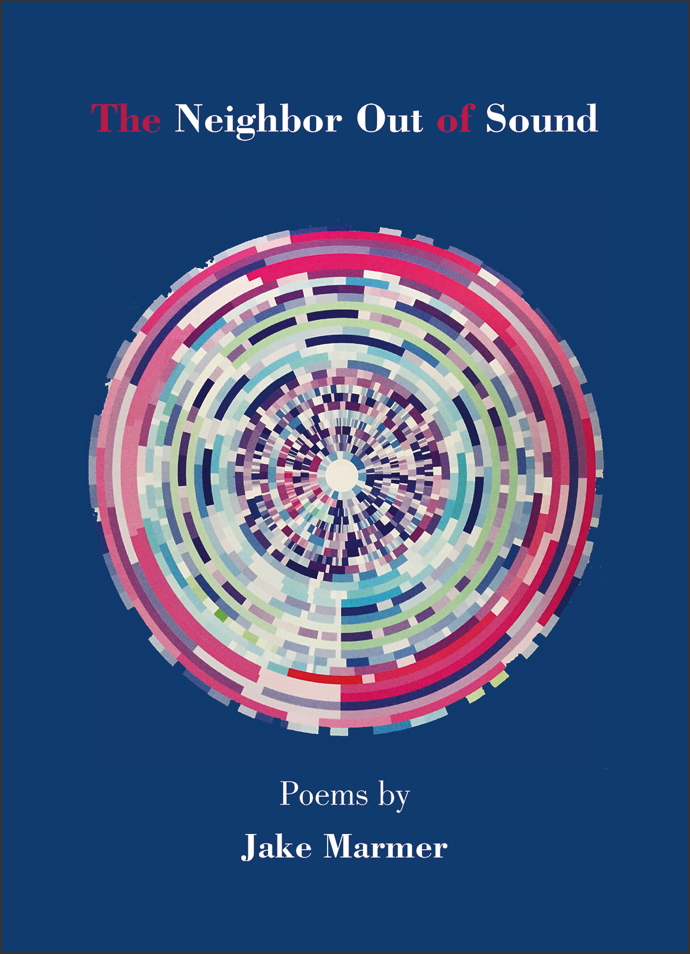

And then I left, and then I stumbled to the subway. I’d only taken a few steps when I remembered that, in the waiting room, someone had told me to look outside the door. “The Rebbe’s not the first wise person to have a minyan here,” he’d said. I looked, and this is what I saw.

I never expected to be on the Upper East Side. But I guess G-d has plans for us all, even those ghosty areas of Manhattan.

(And yes, I know it’s weird to call poems that are printed in a book “improvisations” — it sounds like a nice way of saying unedited. But there’s a spontaneity to these verses, a connected randomness like a really good middle-of-the-night dvar torah that comes at the end of a Shabbos tisch, where your brain connects one thing with another, geography homework with Elijah coming before the idol-worshiping priests, and everything seems to flow together in a way that makes utter sense of the universe.)

(And yes, I know it’s weird to call poems that are printed in a book “improvisations” — it sounds like a nice way of saying unedited. But there’s a spontaneity to these verses, a connected randomness like a really good middle-of-the-night dvar torah that comes at the end of a Shabbos tisch, where your brain connects one thing with another, geography homework with Elijah coming before the idol-worshiping priests, and everything seems to flow together in a way that makes utter sense of the universe.)