When you write a story, make it about you. Even if it’s about the shidduch crisis. Even if it’s about the Baal Shem Tov. Start with something that means something to you — a statement, a feeling — and let the story grow from there.

A lot of writing classes will tell you to show, don’t tell. That’s good advice, but it isn’t all true. Telling can be a great tool. But in order to tell the audience what you’re thinking or how you’re feeling, you need to take us through the steps of your experiencing this.

And that’s a lot more easily experienced by telling your reader where you were at one point — not just saying you were, say, a college dropout who refused to eat any food aside from bacon, but describing why bacon was so important to you, telling us in detail how each stick was as long as your hand and had little bumpy ridges and ghostly shivers of white fat, and how the reason you ate so much of it was that your college was Porgsley’s School of Pig-Thumpin’ and they gave it free to all the students, and not only does it conjure memories of happier times, but you sneak onto campus and get free bacon and it’s the only time you ever see all your old friends.

Then — and only then — are we prepared to hear about how you gave it all up to be kosher.

We, as frum writers, as Jewish writers, or just as writers who are somewhat preoccupied with issues of faith and belief, are especially susceptible to epiphany. I saw the light! G-d spoke to me!

It’s such a tempting idea, this sudden mental switch or a realization-from-on-high that affects you in a way that makes you stop in your tracks so fast that dust clouds rise around your ankles, and then — for reasons that are often hard to explain and sometimes so totally otherworldly that you can barely explain them to yourself, let alone write a story about them for other people — you’re a different person than you were before.

That’s the essence of a story. Or, it’s very close to being the essence of a story. What’s missing from your revelation is the story itself.

**

Remember The Matrix? Remember when Keanu said “whoa” a lot, and then Morpheus explained to him for like 20 minutes that all of humanity is living in little electric aquariums and the machines took over and we’ve forgotten what it’s like to rebel….and, my friends, that is a good freaking way to tell.

But The Matrix also made the telling itself into a story. Instead of just saying that there was a war between people and robots and people are sleeping through their lives and they don’t realize it, the filmmakers told it as a process. First the situation was this. Then this happened. Then, here’s another element that complicates it. They explained the situation like building a building, telling one step at a time…and then, before you know it, you’ve got a whole freakin’ skyscraper of a story.

**

Stories don’t have to be about somebody changing. That’s not where the energy of a story comes from — the energy comes from tension, from the moment just before whatever’s going to happen, happens. Sometimes it will happen. Dorothy rescues the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, Moses tells Pharaoh to Let My People Go.

And sometimes it doesn’t happen. When Joseph’s brothers come to him, they tell him there’s a famine, they need his help — the whole time they’re begging him for food, we aren’t thinking, Is Joseph going to feed them? We’re thinking, Is Joseph going to reveal his true identity? When he sends them away, with the troubling mission of bringing back his brother, the tension mounts. The question is still, is Joseph going to disclose the truth, but now it becomes, Is he going to tell his brothers the truth AND what the hell does he need his baby brother Benjamin for?

Stories within stories.

But if every story were about a character changing, they’d be predictable. They’d be boring. Sometimes stories do get that way. We know this as readers. Instead of thinking, is the main character going to realize he’s wicked and have a change of heart, we’re thinking, when’s he going to get to the change of heart and make everything better already.

Recognize that feeling? That’s called boring.

To keep the reader on her toes — and, even more importantly, to keep ourselves on our toes — nothing can be predictable. We need to keep ourselves guessing.

At this point, you’re probably saying, duh, Matthue, all you do is watch Buffy the Vampire Slayer and read books, your life is more fiction than nonfiction, how do you build character moments in my True Real-Life Personal Essay? Well, it’s true that you’re probably not as exciting as Buffy,* but that doesn’t mean anything. I forget who first said this, but there are some people who can tell a story of walking to the corner store to buy bread and make it more tense and emotional than your mother dying, and there are some people who can talk about their mothers dying and it sounds as boring as going to the corner store.

When you start to write, set your boundaries. Tell your audience what’s at stake. If it’s a blind date, tell us about every date you’ve been on before. Is this your first? That raises the stakes even more. Tell us your dream date as a child, tell us all the ways that this date is nothing like that — for worse or maybe for better. If it’s about your kid waking you up in the middle of the night, tell us how desperately you’re craving sleep, how bad the day has been, or how good, or how you haven’t seen them at all. If it’s a story about being hungry in the middle of the night, tell us about what you ate that day, or didn’t eat that day. Tell us how much you love, say, chocolate-covered Bamba. Tell us how it’s the last packet and you and your parent/child/wife/roommate are fighting over it (or if they’re asleep, tell us how bad they’ll kill you if you eat it). Look for tension. We’re in galus, the world of exile — tension is really not that hard to find. It’s everywhere.

And if there are problems, embrace them. There’s a rule that I’m making up as I write this that says that the sadder or crazier or weirder you look on paper, the more awesome you are in real life. There’s a reason Tom Cruise is okay with getting beat up horribly in his movies, or that Woody Allen always makes himself look pathetic (well, don’t use Woody Allen as a barometer). You’re the hero. Make yourself vulnerable. Make stuff happen to you. As far down as you push yourself as a character, that’s how far you can rise up your story.

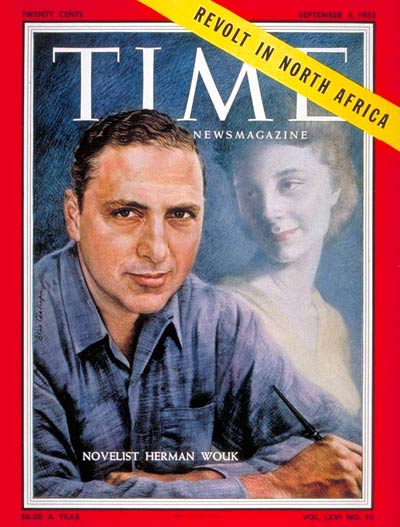

, and one of the most-watched TV miniseries ever. He’s been friends with actors, presidents, and even

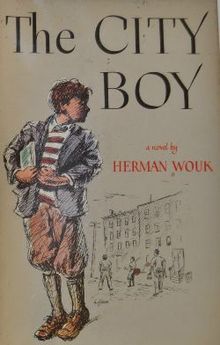

, and one of the most-watched TV miniseries ever. He’s been friends with actors, presidents, and even  Perhaps the ingredient he’s most generous with is wisdom: for despite Herbie’s fumbles in The City Boy, and Norman Paperman’s foolish hotel investment in Don’t Stop the Carnival, there’s always a little wink and a nudge to the reader, a shared grin as if he’s saying, I went through this, I made these mistakes, and I might have screwed up but I got a good story out of it.

Perhaps the ingredient he’s most generous with is wisdom: for despite Herbie’s fumbles in The City Boy, and Norman Paperman’s foolish hotel investment in Don’t Stop the Carnival, there’s always a little wink and a nudge to the reader, a shared grin as if he’s saying, I went through this, I made these mistakes, and I might have screwed up but I got a good story out of it. family who moves to America, assimilates, and winds up in an influential position in the White House. More than anything else, Wouk just knows a good story.

family who moves to America, assimilates, and winds up in an influential position in the White House. More than anything else, Wouk just knows a good story.