I didn’t know what I was going to say to my kids this morning. Each of them is at a different point of comprehension: The election didn’t turn out the way we wanted. That guy who was being mean to girls won the election.

Women can do anything they want to, but there’s not going to be a woman president quite yet.

I prayed in English this morning. I mostly know what the Hebrew words mean, but my brain needed something simpler, more easily digestible, something I could believe in without asking myself How could this happen? and Do so many people really think this way? and Why is there so much hate in the world? The verses came fast and hard. We are but dust. Not for our sake, but for Your compassion. The rule of man over the animals is nothing, for all is but a fleeting breath.

By the time I finished the sun had risen, it was morning for real. I started with the 6-year-old. She wouldn’t budge, she was dead to the world, and I didn’t have the heart to make her — I’d woken at 5, lay in bed for an hour, unable to summon the courage to move. The Shulchan Aruch says you have to start the day like a lion, ready to pounce on whatever comes, but today I’d felt like prey, not predator. I would let her sleep a little longer, spend another 5 minutes in a place where a woman might still be president and not someone who assaulted them.

The 8-year-old was more responsive. She leaped up, brushed her hair from her eyes, and said, “Today is Vampire Day.”

Oh, good. I didn’t have to tell her, she already knew.

Umm… “What do you mean?”

“My friends and I are dressing up as vampires, so I need a brooch. Can you find me a brooch?”

A, I do not have any brooches lying around. B, I actually have no idea what a brooch is and, though it might expand my knowledge, I’m not sure a simple Google image search is gonna produce the desired object in a usable form. C, do vampires wear brooches?

D, is this the first morning of a world controlled by an orange sycophant?

We agreed on an ensemble (her uniform, but presented in a slightly vampier way — collar turned up, maybe?). Somewhere along the way, I mentioned to her, Hillary lost the election.

“Oh.” Disappointment and confusion flickered alternately across her face. “So that means Trump is going to be president?”

“Im yirtze Hashem.” If G-d wills it. He could die soon, I thought to myself. He’s old, who knows what he’s been through. Or the revolution could happen. Or he could do something monumentally stupid and the Electoral College could step in, vote in Paul Ryan as an emergency candidate, do something, anything, to save us from ourselves.

“What’s the Electoral College?”

The ditches I dig myself into.

“So when we vote for president, we’re not actually voting for the president. We’re picking someone else — say, we’re voting for Ani,” I plucked a doll at random, “and in a few weeks Ani is going to go and vote for president for real.”

“Papa, but why?”

“So that if someone really dangerous or evil gets elected, there’s still someone to stop them before they really get elected…but, uh, that doesn’t really ever happen…”

She was looking at me the same way she did when I tried to explain animal reproduction.

A moment of deliberation. Then: “Papa, you’re so silly,” and a grin breaks out.

Not for our righteousness, O L-rd. Not for anything we’ve done, but because of Your generosity and compassion.

So she didn’t completely understand, but that’s about on par with the rest of America. A few minutes later, I go downstairs to wake up the other kids and break it to them. The six-year-old screws up her face, crosses her eyes, sticks out her tongue into a popsicle shake and jams her finger up her nose. “Well, THAT doesn’t make any sense,” she says.

Two minutes later, we are locked in a wrestling match, with her on my stomach and the 2-year-old cheerily perched on my face.

There’s no happy ending to this post. The next four years might suck, and they might suck bad. Or they might not — for all the jejune awareness of how politics really work, you can’t tell another country you’re building a wall and now they have to pay for it; that didn’t even work in kindergarten when Tim Shaw stole my snack and so I figured I would be able to just take his. The president really isn’t that powerful, and in recent history the people who actually hold our nuclear codes have a lot more sense than the people who ostensibly have the power to launch them.

When I broke up with my first girlfriend, I remember how full the world seemed of her. Everywhere I looked and everything I thought about related back to her — the toys in my room we’d played with, the apple juice boxes we’d smuggled to each other. (It was first grade.) (Mostly-true story: She moved away in first grade, but we wrote each other letters for a little bit; to the best of my knowledge, she became a covert operative for the CIA.)

But the more time I spent away from her — the more of my life became filled with not-her things — the easier it was on my tender little heart.

Last night, as the results were pouring in, my wife was out for her first night out since the baby was born. I was left at home with an infant who does not inherit my predilection for bottles — and, for good measure, a beat-up old Saab outside whose alarm went off whenever another car passed by. Yes, bad news was hurling at me like tomatoes toward Fozzie Bear on a good night. But it was all relative. The infant in my arms, who knew nothing of political pain, bellowed at the top of her lungs for milk. And then she had it. And then she was asleep.

Right now we are bellowing. Right now it feels like the whole world — especially if you are at an office job with Internet access, especially if your only way of staying in touch with your friends is them posting memos about the end of the world.

But, as the ancient rabbis said (well, it was on Buffy), we’ve faced the end of the world once or twice before. We’ve pulled through.

It sucks to tell your kids. It sucks to tell yourself. But we’re going to pull through again.

photo: “I think I’ll start a new life” by Noukka Signe

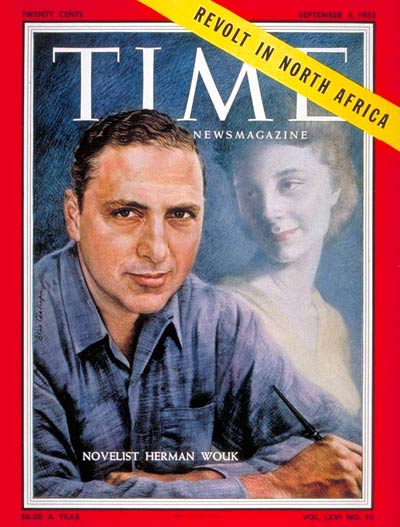

, and one of the most-watched TV miniseries ever. He’s been friends with actors, presidents, and even

, and one of the most-watched TV miniseries ever. He’s been friends with actors, presidents, and even  Perhaps the ingredient he’s most generous with is wisdom: for despite Herbie’s fumbles in The City Boy, and Norman Paperman’s foolish hotel investment in Don’t Stop the Carnival, there’s always a little wink and a nudge to the reader, a shared grin as if he’s saying, I went through this, I made these mistakes, and I might have screwed up but I got a good story out of it.

Perhaps the ingredient he’s most generous with is wisdom: for despite Herbie’s fumbles in The City Boy, and Norman Paperman’s foolish hotel investment in Don’t Stop the Carnival, there’s always a little wink and a nudge to the reader, a shared grin as if he’s saying, I went through this, I made these mistakes, and I might have screwed up but I got a good story out of it. family who moves to America, assimilates, and winds up in an influential position in the White House. More than anything else, Wouk just knows a good story.

family who moves to America, assimilates, and winds up in an influential position in the White House. More than anything else, Wouk just knows a good story.