Here's the moment I knew Matisyahu had stopped being a Jewish phenomenon and entered the realm of pop culture. My sister, who was living deep in the Bible Belt, told one of her non-Jewish friends that I'd become Orthodox. "Oh," he said. "Does that mean he looks like that Matisyahu dude?"

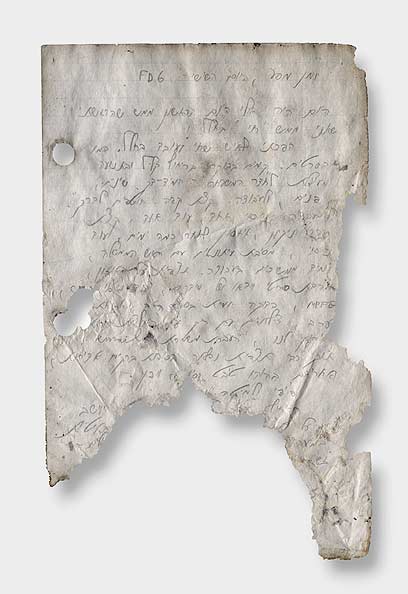

Portrait by Schneur MenakerMatisyahu

Portrait by Schneur MenakerMatisyahu might not be the official face of Judaism in America, but he's a lead contender. The reggae-singing phenomenon, a

baal teshuvah who became Orthodox in his twenties, might have the most recognizable profile in pop music due to his beard alone. After learning to be religiously observant through

Chabad, Matisyahu expanded his learning to include the teachings and prayer styles of

Breslov, Karlin, and other Hasidic groups in addition to the Chabad rebbes.

Matisyahu's third studio album,

Light, comes out August 25 -- almost six months after its

expected release, and three and a half years since his last album, the pop-infected, Bill Laswell-produced

Youth, which sold over half a million units.

Since then, Matisyahu has gone back to the basics. He has a new songwriting cave (an old warehouse in Brooklyn's Greenpoint neighborhood), a new synagogue (a

Karlin Hasidic synagogue, where the prayers are shouted at the top of your lungs), and, perhaps most radically, a new sound to his music. His new songs, both on last year's single

Shattered and on

Light, still have the reggae influence that dominated his earlier albums. Yet new album's tone is darker, more varied, and beat-driven. "One Day," the album's first single, has a dreamy, summertime quality that is equal parts Bob Marley playing acoustic and "Eye of the Tiger"-like '80s jams. "Master of the Field" is an electronics-heavy jam that brings his vocal beatboxing to the forefront.

MJL spoke with Matisyahu and learned out about his new band, the stories behind the

Light songs that he isn't telling anyone else, and why Matisyahu just can't stop loving God.

MJL: A while ago, you told me how Israel right now is for Jews how Greenwich Village was to hippies in the '60s -- wild and innovative, the only place where Judaism's really alive and mutable and organic, whereas in the United States, Jews are sort of stagnant. Do you still feel that way?Matisyahu: Anywhere in America where I happen to be -- Crown Heights, Willamsburg -- in any Jewish community, it seems like there's one type of Jew. There's pressure to fit in and dress a certain way, talk a certain way, and if you don't do that, it's almost like you're not Jewish. And

then in other places, there are a lot of different types of Jews -- and, in those places, you lose the intensity of belief and of observance and of the lifestyle. And that's only among religious Jews. In America, you can be Jewish and elect not to have anything to do with Judaism.

In Israel, even sitting in the airport, you're among a hundred different kinds of Jews, and it's amazing. It's inspiring. Everyone's doing their own thing, but it's

not just their own thing -- they have a whole community of people backing them up.

Then you come back to America, and you really feel that we're a small minority of people. We're trying to hold onto something that doesn't necessarily fit into our hands. In Israel, Judaism is alive. It's a real, tangible, living thing.

Is that where the titles come in? Your last E.P. was called Shattered, and it seemed like the very small prelude to something a lot bigger. And then the new album's going to be called Light.Yeah, it all kind of figures together. There's a

Kabbalistic idea of the first world being shattered, utterly destroyed, and the second world -- the world we're in right now -- being a tikkun, a fixing, of the first one. Are you an artist?

Do you mean --I mean, like, a visual artist.

I draw a little, but I don't really know what I'm doing.I know what you mean. That's where I am, too. (Laughs.) So when you look at something without light, it looks dead. It's two-dimensional, without any depth or substance. If there's no shadows and no light twisting off of surfaces, it's like it doesn't exist at all. Just like that, when a person looks at the world, it's like it's dead. Then, with light and a backdrop, everything becomes revealed, and their depth comes out.

That's what

Shattered was about. Naming the E.P. "Shattered," it was about stopping running away.

I was running for the past few years, running nonstop. My career, my marriage, my kids -- but mostly my career. This past year I've spent mostly at home, going to

minyan, working on my record, jamming in my studio.

The songs on Shattered, and the stuff that's been released from the new album so far, is all way different than anything you've done before -- it's more beat-driven and electronic. Why the change?The foremost changes were all vocally. Musically, we've used elements of reggae, but it's not traditionally reggae. If you listen to my first single, "King without a Crown," it's not reggae -- the beat isn't a traditional reggae rhythm. It's not really a reggae song.

Your vocals, though, really are very reggae-influenced...It's true. When I sing that song, a lot of my earlier songs, I'm using a Jamaican accent. When I was first developing my singing, I was only listening to reggae. When you listen to only one kind of music, that style penetrates you. A lot of the big reggae singers, the people who've been around for years, they take new techniques and integrate them into their singing. These days, I'm listening to a lot less reggae. I'm listening to a lot of different things.

Do you feel like you need to keep a certain level of reggae influence in your music? Are you feeling pressure to keep it or to move away from it, one way or the other?In this record, I allowed myself to drop it. Reggae isn't the prevalent music style I'm listening to these days. Also, I've been taking voice lessons, developing my voice to go in different directions as well. I'll hold onto the reggae in some places -- others, I'll just let it go.

Musically, I allowed for all my interests to come together. I've been writing the music for Light in a different way than we've ever written before. [Guitarist and musical director] Aaron [Dugan] and I -- we wrote all the songs together, all very free-form. He'd play guitar, and I'd beatbox and sing. We'd go into the studio and start jamming for an hour and a half. We'd hit record, and then when we finished, we'd play it back and listen to it.

Then we had a bunch of guests on the album. Ooah from

Glitch Mob did a bunch of electronic stuff. We had a producer from Jamaica,

Stephen McGregor, and another, Motivate. People are like, "He's lost his reggae thing, he's not reggae anymore -- " It's ironic, [McGregor] is this 17-year-old kid who's producing Sean Paul, Trevor Hall, he's a singer-songwriter in the Marley mold, and another producer who's done Fishbone.

You write really candidly about God, praying, and your relationship with your religion. Does it feel different to write, or less confidential, when you know a million people will hear it? How do you get to the safety of trusting yourself?

You write really candidly about God, praying, and your relationship with your religion. Does it feel different to write, or less confidential, when you know a million people will hear it? How do you get to the safety of trusting yourself?It's entirely different. My band, my writing, everything. We changed the band around after

Youth. There's a new bassist and a new keyboardist. Building the new band has been a two-to-three-year process.

And then, lyrically, my teacher, mentor, friend Ephraim Rosenstein -- he takes a

Chabad ideology and compares it to Breslov ideology -- he asks what's important in each one -- and then he brings in other philosophies, contemporary philosophers like Nietzsche, and he takes wider themes from

Rosh Hashanah and

Yom Kippur. First we break down the themes into simple ideas. Then we bring in stories to illustrate these ideas.

That's kind of what Rebbe Nachman did. He says that the most important ideas can't be transmitted as abstract ideas, that they have to be transformed into stories.Definitely. I did a project for the John Lennon

Save Darfur project to end child slavery, and I'd been studying a lot of Breslov stories, and I looked for a way to link these together.

I came up with two children -- child soldiers in Africa, they've been forced to fight a war. They escape their army, and then they're lost in a forest, like in [Rebbe Nachman's] Story of the

Seven Beggars. One song is called "We Will Walk" -- it's about continuing on, no matter what happens. "Two Child One Drop," from

Shattered -- it's pretty clear, it's about killing someone, which Hasidic tradition compares to embarrassing someone. It's like putting a gun up to someone's head and making them do something.

Is it something that you expect people to pick up on and intuit when they listen to your music -- or do you think they're just going to go, wow, that's some intense violent imagery, and move on?I don't know. A lot of it's not explicit in the songs, Africa or Rebbe Nachman -- maybe when they read this interview with you, they'll get it. But I think the ideas come through.

Rabbi Rosenstein and I came up with thirty categories of ideas, of stories -- and then we pared the concepts down to words. Then we went into my studio in Green Point, just Aaron [Dugan, Matisyahu's longtime guitarist] and I -- Aaron would play and I'd beatbox. We'd jam for an hour without stopping.

Then I'd listen to the sound. It was some really dark stuff we were coming up with. I'd take the music, write down some lyrics, and form the songs that way. We brought in other people -- I flew to Jamaica, where we brought in [legendary drum and bass production team] Sly and Robbie. We had the oud player from

The Idan Raichel Project, Yehuda Solomon from

Moshav singing Hebrew on top of me. The songs ended up in a totally different place from where it started.

Has all the new stuff you're doing transitioned into your live show?A lot of what we've been doing is totally new. We've abandoned writing set lists in advance. We're abandoning expectations about what the show should be -- we have moments of in-between songs and improvs that become longer than the songs themselves. There's better dynamics. People drop out, we get quieter than we've ever been. The space and the music almost do the job for us. The lyrics are the smallest part.

Are you nervous about the reception of the album? It feels like a lot is riding on this new record -- it's really experimental, but it's also really personal.In the end, when someone listens to the record, they won't hear that story I told you. I guess the worst reaction could be, "Aw man, this is a love story, Matisyahu isn't writing Jewish songs anymore."

Or everyone might love it, and decide you're not writing just-Jewish songs, but universal songs -- songs that hit everyone in the same way. There was one song about a boy dying in a desert, telling a girl to carry on without him. I was playing some of the songs for my wife's family, and my sister-in-law was like, "What girl is this about? It isn't about my sister." In a way, that's the best compliment I could get.

Every time I visit the store -- whether it's a 3-hour trip to pick out a new video camera or a quick run-in for some batteries -- I come out with a new story. Sometimes it's as simple as the Satmar Hasid at the checkout counter asking me what I think of the

Every time I visit the store -- whether it's a 3-hour trip to pick out a new video camera or a quick run-in for some batteries -- I come out with a new story. Sometimes it's as simple as the Satmar Hasid at the checkout counter asking me what I think of the  be affiliated with B&H? If he stopped to pay attention to the person I am, and not just the way I look, maybe he'd be a bit less stereotypical and bit more astounded. I'm a freakin' Hasidic Jew who writes films, dude! I'm more than my payos! Just because I'm Hasidic, it doesn't mean I know every other Orthodox Jew in New York. Or where they work.

be affiliated with B&H? If he stopped to pay attention to the person I am, and not just the way I look, maybe he'd be a bit less stereotypical and bit more astounded. I'm a freakin' Hasidic Jew who writes films, dude! I'm more than my payos! Just because I'm Hasidic, it doesn't mean I know every other Orthodox Jew in New York. Or where they work.

then in other places, there are a lot of different types of Jews -- and, in those places, you lose the intensity of belief and of observance and of the lifestyle. And that's only among religious Jews. In America, you can be Jewish and elect not to have anything to do with Judaism.

then in other places, there are a lot of different types of Jews -- and, in those places, you lose the intensity of belief and of observance and of the lifestyle. And that's only among religious Jews. In America, you can be Jewish and elect not to have anything to do with Judaism. You write really candidly about God, praying, and your relationship with your religion. Does it feel different to write, or less confidential, when you know a million people will hear it? How do you get to the safety of trusting yourself?

You write really candidly about God, praying, and your relationship with your religion. Does it feel different to write, or less confidential, when you know a million people will hear it? How do you get to the safety of trusting yourself?

professional poet) and attire (him: black mock turtleneck; me: probably something 20 years old and paisley) and not exactly fitting in with the rest of the crowd, although fitting in in the way that we were all of us mismatched, all of us more-or-less haphazardly tossed into the melting pot that is a Chabad House.

professional poet) and attire (him: black mock turtleneck; me: probably something 20 years old and paisley) and not exactly fitting in with the rest of the crowd, although fitting in in the way that we were all of us mismatched, all of us more-or-less haphazardly tossed into the melting pot that is a Chabad House. And, no matter

And, no matter  It's been a long Thanksgiving weekend. I know, today's Monday and we're back in work mode, but it feels like the weekend isn't over yet. It was a hard holiday; harder for other people than for us, but thinking that doesn't make it any easier. At our Thanksgiving table was my cousin's boyfriend, who's from Mumbai and whose parents are safe, but who still hadn't heard from his friends; my wife, whose sister is scheduled to go on vacation in India later this week and who's still thinking of going; and all of us, most of whom aren't religious, though we've all been guests at a Chabad house at one point in our life or another.

It's been a long Thanksgiving weekend. I know, today's Monday and we're back in work mode, but it feels like the weekend isn't over yet. It was a hard holiday; harder for other people than for us, but thinking that doesn't make it any easier. At our Thanksgiving table was my cousin's boyfriend, who's from Mumbai and whose parents are safe, but who still hadn't heard from his friends; my wife, whose sister is scheduled to go on vacation in India later this week and who's still thinking of going; and all of us, most of whom aren't religious, though we've all been guests at a Chabad house at one point in our life or another. Not emotionally (although in conversation he is raw and perceptive -- he always seems to know what you're thinking, and he's two steps ahead of the question you're about to ask) and not physically (on the night we speak, he's in Norfolk, Va., where soon he will play to a packed crowd of 1,500 in a refurbished 1920s theater). On Nov. 18 he'll be at the Club Nokia in Los Angeles.

Not emotionally (although in conversation he is raw and perceptive -- he always seems to know what you're thinking, and he's two steps ahead of the question you're about to ask) and not physically (on the night we speak, he's in Norfolk, Va., where soon he will play to a packed crowd of 1,500 in a refurbished 1920s theater). On Nov. 18 he'll be at the Club Nokia in Los Angeles.